Painting in Extremes (Tips for artists)

by Lucia deLeiris, The Guild of Natural Science Illustrators Journal 2007

(Article and illustrations)

Gazing through the window I watch the icebergs drifting into the bay,  brash ice floating around the few stationary grounded ones. A lone penguin pops out of the glassy surface like a cork, lands on an icy ledge and peers around with beady eyes.

brash ice floating around the few stationary grounded ones. A lone penguin pops out of the glassy surface like a cork, lands on an icy ledge and peers around with beady eyes.

Leaving my studio window at the Antarctic Palmer Station, I put on my boots and pack filled with watercolors, trudge over the rocks behind the science station and up the glacier. Sitting on my square of foam, I laid the palette on the ice and the Arches watercolor block in my lap. I began to lay in the wash for the sky. When I went to mix a touch of cerulean to the puddle in the palette and swirled it around, it suddenly became all grainy. How could sand have gotten into my paints way up here?! As it clumped, it suddenly it dawned on me… the paint was freezing! What to do? ! I looked at my watercolor and there the delicate sky wash had begun turning into a starry pattern. Even THAT was freezing!

I had successfully painted with watercolors from the rocks along the shore below, not realizing that the mass of ice under me sitting on the glacier would drop the air temperature by just a few degrees… to below the freezing point.

Sponsored by the  National Science Foundation in 1985, and living at Palmer Station, on the Antarctic Peninsula, I was there to illustrate a book on the ecology of the Peninsula. This was the first of three such trips I took in the NSF Antarctic Artist and Writers Program. For the most part of the Antarctic summer (November through February), it was in the thirties (Fahrenheit) and just warm enough to work with watercolors. Not knowing what to expect ahead of time, I had made a painting tent with a vinyl window (the same vinyl as used in sails of windsurfers.) It had a propane heater which sat inside a collapsible aluminum box, ventilated through heat resistant tubes (the type used in

National Science Foundation in 1985, and living at Palmer Station, on the Antarctic Peninsula, I was there to illustrate a book on the ecology of the Peninsula. This was the first of three such trips I took in the NSF Antarctic Artist and Writers Program. For the most part of the Antarctic summer (November through February), it was in the thirties (Fahrenheit) and just warm enough to work with watercolors. Not knowing what to expect ahead of time, I had made a painting tent with a vinyl window (the same vinyl as used in sails of windsurfers.) It had a propane heater which sat inside a collapsible aluminum box, ventilated through heat resistant tubes (the type used in  airplane engines). This was a fantastic set up for days when I would spend the whole day out painting, as once set up, it was downright cozy inside. On a drizzly gray day I could paint comfortably from a low stool with a cup of tea sitting on my heating box. However, more often I went out in the field without it as it was cumbersome to haul out and set up, particularly in any wind. I would often be dropped off for the day by zodiac on small islands nearby with a hand-held radio. On days without the tent, I would manage to sketch and paint by using fingerless wool gloves. These, along with many layers of clothes to keep my core temperature up was sufficient in those temperatures as when the air was dry and windless, it felt much warmer.

airplane engines). This was a fantastic set up for days when I would spend the whole day out painting, as once set up, it was downright cozy inside. On a drizzly gray day I could paint comfortably from a low stool with a cup of tea sitting on my heating box. However, more often I went out in the field without it as it was cumbersome to haul out and set up, particularly in any wind. I would often be dropped off for the day by zodiac on small islands nearby with a hand-held radio. On days without the tent, I would manage to sketch and paint by using fingerless wool gloves. These, along with many layers of clothes to keep my core temperature up was sufficient in those temperatures as when the air was dry and windless, it felt much warmer.

Painting on my second trip to Antarctica ten years later was a different story. There I was planning to do paintings of the more extreme Antarctic landscape. I flew from New Zealand, eight hours south to McMurdo Station on the Ross Sea. This, being further south, was much colder and being the early Austral spring (August) was in the minus fifties when I arrived. The first time I set up my painting ten, its vinyl window shattered in the cold, so I put it away and set out to find another way to work.

Working from various field camps in the area, I was sometimes able to paint from windows of heated Quonset huts. The challenge came when I ventured out in the frigid air. One day the wind chill dropped the perceived temperature from the actual minus 51 degrees to minus 114! During those days, I found my most useful tool was my visual memory. I had to keep moving to keep my core temperature up. When it warmed to the minus 30’s, I could do quick sketches with a pencil held through thick gloves with polypropylene liners. I sometimes worked from a tracked vehicle, whose heater would barely manage to bring the temperature up to the freezing point. As a result even then I need a few tricks to do watercolor. To keep the wet brush from freezing, I would bring not the usual water bottle, but rather a thermos of near boiling water. I could then warm the cold water in the cup periodically and keep the brush thawed. When not carrying a thermos, I found a dash of vodka in the water lowers the freezing point and can work as well (as long as you don’t drink it first!)

For my fingers, I could get away with thin polypropylene glove liners under woolen fingerless gloves. (both available in winter sports stores). If needed, I put a chemical hand warmer inside the outer glove over my palm and this would keep my fingers warm enough. Mobility was somewhat hampered by the glove liners, but very little. As for medium, I found the one I could always fall back on was pencil, for sketches, color and value notes. This technique was used by some of the early Antarctic explorers such as Edward Wilson who accompanied Scott to the South Pole in 1912. Once above 32 degrees, I could use watercolor. Pastels worked but were not easy to handle with gloves, so I usually left those back in the heated camp to use inside the hut.

The progressing spring season warmed the air temperature up to minus 20 degrees, (quite balmy compared to -50 or even -30) (Yes, one can feel the difference between these temperatures, though I could not imagine that before I went south). Once at -20, I could sit on my aluminum tripod stool for long periods of time without having to get up and move around for warmth. This luxury corresponded with the emergence of pregnant Weddell seals who one morning populated the sea ice around the field camp where I was staying. What a surprise to wake one morning and find the ice dotted with seals! With ice drill in hand to test thickness, I went with a writer companion on hikes, avoiding the emerging cracks through which the seals had arrived. I was able to sit and sketch from these models which soon bore scrawny pups with big marble eyes. For sketching moving animals I always find the good old wood pencil to be the most versatile and practical medium. It certainly is the simplest as well. At minus 20, there was no chance of doing watercolor. My tripod stool kept me off the snow and ice as well as in a comfortable sitting position for longer working periods. For shorter stints, or to keep the weight down for longer hikes, I would carry a 16” square piece of foam to sit on. This helped with the cold as well as comfort for sitting on ice or rocks.  When color notes are necessary, colored pencils would be practical though I find making color and value notes in pencil sufficient and simpler. One night when I was about to turn in, I noticed black dots appeared on the horizon, growing larger. They turned out to be 26 Emperor penguins heading straight toward our field camp. Once arrived, they stood around for several hours before continuing on in their inland direction. The midnight sun cast its golden glow on their breasts, and gilded Mount Everest, the volcano behind, turning the snow and ice a soft violet in the shadows. This was not a moment to be thinking in black and white! In such a case I don’t try to do any complete drawing in the field, as with such a fantastic opportunity I wanted to capture as much as possible to work from later. Gesture sketches and color notes did the trick best.

When color notes are necessary, colored pencils would be practical though I find making color and value notes in pencil sufficient and simpler. One night when I was about to turn in, I noticed black dots appeared on the horizon, growing larger. They turned out to be 26 Emperor penguins heading straight toward our field camp. Once arrived, they stood around for several hours before continuing on in their inland direction. The midnight sun cast its golden glow on their breasts, and gilded Mount Everest, the volcano behind, turning the snow and ice a soft violet in the shadows. This was not a moment to be thinking in black and white! In such a case I don’t try to do any complete drawing in the field, as with such a fantastic opportunity I wanted to capture as much as possible to work from later. Gesture sketches and color notes did the trick best.

None of this experience did me any good when I found myself in Death Valley painting in oils where the sun beat down through 110 degree air. Field gear there included a broad brimmed straw hat, sunscreen, and neutrally tinted sunglasses. To combat the heat I discovered a useful technique. Over a loose tank top, I wore a long-sleeved cotton shirt. Putting some of my ample drinking water in a plastic bucket, I could periodically submerge the shirt, wring it out and put it on. In the dry desert air, the evaporation kept me comfortably cool for painting.

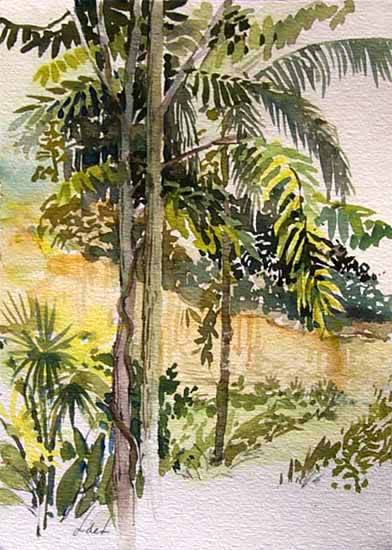

This system, great for Death Valley, did me no good in the Amazon River region where the air was already saturated with humidity. There, by the ochre colored river, wet clothes stay wet, hot and sticky. There I soon found the best way to avoid the heat of midday is to avoid being out at midday altogether. There is a good reason the local Amazonians are up and about at 6 AM for sunrise, reserving three or four hours at midday for resting. I wasted no time adapting to that local rhythm, saving the best parts of the day for painting. With no experience in hot humid conditions, I thought I had covered the major painting hurdles by bringing a sunhat, bug repellant, and sunglasses. I carried a lightweight plastic folding palette and spare tubes of watercolors. Soon I found that the paints in the palette wouldn’t dry, instead taking on the consistency of molasses. I was constantly wiping up runny paints. Because I was in the Tahuayo Lodge , where the rustic walkways were lit by kerosene light, I suspended the palette well above a lamp all night so that by morning the paints were hard and dry. “Problem solved” I thought. Then, thirsty, halfway down the forest trail I unzipped my pack to pull out a water bottle. It was covered with cadmium yellow, red, and cerulean blue paint, flowing down the plastic in thick streams. The humid air alone had softened them. On a subsequent trip I tried the hardened pan watercolors, but even they softened and ran. The next time I will bring an empty palette and tubes of paint, from which I will dispense just enough to use, each time wiping the palette clean.

Humidity affected the paper there as well. The Arches watercolor blocks worked well, but once cut off the block, the single sheets would absorb humidity over time and become undulated. I learned to put them into air tight sealable bags and this worked fine. I also included a moisture absorbing packet. These I save when they arrive in the mail with shipped items but I have heard that photo supply stores sell both these and air-tight bags.

I find that despite hot, oozing melting paints, warping paper, freezing washes and numbing fingers, nothing is quite so satisfying as sketching in the field. Travels whose impressions I capture with brush in hand have always carried the best memories.